Isis Nusair (IN): How did you start making movies?

Michel Khleifi (MK): It happened by chance. There was nothing in our life in Nazareth that would have prepared me to be a filmmaker. The films we saw, like all the children our age in the 1960s, were popular and commercial. This was our only chance to breath in the “Nazarene ghetto.” Closure was imposed on us by the Israeli occupation through its cruel military rule that banned us from leaving Nazareth without permits. The world used to come to us through these films and some leftist newspapers and magazines.

There was one screening hall for thirty thousand people in my small town. They used to also screen films at the French and Spanish missionary schools. I loved theater since I was a kid and used to dream in a naïve way to study it one day. In the mid 1960s, I saw Elia Kazan’s film, America, America. The film tells the story of a Greek family from Turkey before WWI, and before the massacres and ethnic and religious cleansing committed by the Ottoman and later Turkish authorities against the Armenians, Syriacs, Christian Arabs, and of course large numbers of Greeks. In the film, the family wants to smuggle its wealth via its oldest son who dreams to immigrate to the United States of America. This fictional family resembled to an extent my family that comes from a similar background: Christian Greek Orthodox. There is a scene in the film of an engagement party that was similar to my sister’s engagement party that I remembered as a child. I was surprised by how Kazan managed to capture the details of that scene. That is when my view of cinema started to change. I realized that it was not only for entertainment, and that it was able to dive into our inner world and capture personal and intimate moments. We are able through cinema to restructure and convey our personal feelings.

I left school when I was fourteen and a half years old. I worked in a garage for five years (two in Nazareth and three in Haifa). My love for theater led me to a strange hobby for my age which was reading plays. Maybe this gave me more freedom to liberate my imagination. Wherever I went, I always had a play with me. At the time, we did not know that knowledge was a capital we carried in our heads. That is when it became clear to me that we need to develop the elements of our culture and knowledge, and how important it is to build a national/cultural/political project that could reach an international level.

IN: Tell us about your studies in Belgium.

MK: When I got to Belgium in the early 1970s, the youth revolution in Europe was at its peak. It was a cultural revolution that swept away with the old and the conservative. Marxist thought from a variety of political and philosophical views dominated the artistic, cultural, and literary European scene at the time. Parallel to that, there was a cultural/political movement in South America that worked on illiteracy and taught people to think critically through teaching them how to read and write. That is when I got the vision to create a Palestinian “culture of the poor” that could stand in the face of “cultural poverty.”

Let us not forget that during that time, the Vietnam War was taking place. This war was important for my generation because the Vietnamese people were able to triumph over an empire and prove to the world that “poor” people are able to win and be creative culturally, politically, and in their struggle. This was a victory over the strongest country in the world. I realized then how important it was to convey the Palestinian experience as a human and just one. I needed to start expressing myself artistically and culturally in order to reach that human level. I had to look for the keys to my personal expression that were a product of the accumulation and richness of the Palestinian human experience itself.

I love Arab culture and I belong to the Middle East, the cradle of human civilizations. Palestine is what got me to love knowledge, art, and cinema. Palestine through cinema got me to reach out to women and women got me to freedom. These are the basic elements of my films. I belong “there” like an orange that bloomed in Jaffa and no more. You can take one branch from Palestine’s oranges and plant it anywhere in the world or vice versa. We take from the world to enrich ourselves. Life is an exchange and enrichment for me and for the other.

I am always looking for people who will liberate language, form, art, politics, and philosophy, as well as techniques and not allow them to freeze. It is important to liberate things and give them an open space to operate. Critical thinking is the base for building a free society and for building culture and mature beings aware of the world around them.

In Brussels I studied how to direct theater, radio, and television. I did not know that cinema was an art that could be studied as well. Since my first year of studies, I was always attracted to cinema students and started to volunteer to work with them. In Belgium, I built myself and my knowledge and discovered hundreds of things. It was a wonderful experience that pushed me into adventures that I did not dream of, and at the same time it brought me back to the world of my childhood in Nazareth.

I remember in one of the visual art history classes, the teacher talked about Picasso’s “blue period.” He showed us some pictures from that period. When I was a child, curfew was imposed on us at night in Nazareth, and the police and border patrol units would ask people to turn the lights off. A man would go around and scream in Arabic, “Turn the lights off.” People, including my father, would paint the lamps with blue watercolors and the color blue will dominate the scene exactly as in Picasso’s paintings. I wondered whether Picasso actually lived through that cruel experience with us; that is the “blue period” of the Palestinian people.

During my childhood years, Palestinian communists paid close attention to culture, poetry, and literature. This resulted in the emergence of Palestinian poets like Tawfiq Zayyad, Samih al-Qasim, Salim Joubran, and especially Mahmoud Darwish. The communists’ newspapers and magazines were an open window to progressive and international literature. That made us feel less alone when facing the Zionist abuse and occupation, and realize that we are part of that same progressive culture and people struggling for their freedom and liberation.

This was the “warm stream” in Marxism that was defended by the Frankfurt School. It said that culture touches the humanity of people and liberates them regardless of ethnic, national or religious identities. This is where the contradiction between cultural work and ideological thought starts. Questions of freedom are the essence: Does freedom have borders or is it without borders? What is the difference between what is moral and what is legal? These questions became the center of my daily thought and where I looked for intellectual answers and later for themes to convey the practical, theatrical, and cinematic experiences.

IN: Why did you start making documentaries and not fictional films?

MK: Cinema is an art that is built on the relation between thought and the eye/camera and what is in front of the camera and vice versa. Is what I see real or is it a staged reality enacted in front of the camera? What is reality? Is it my surroundings or my inner world looking outside? What is the dynamic and dialectical relation between these two worlds? That is how I started posing questions about cinematic form and how to reflect the Palestinian reality without prior ideological pressures. There was another essential element that interested me in regard to how to represent the existential Palestinian experience cinematically. How can I convey the “story” of a people without pictorial memory? What is the intellectual, mental, and temporal path for writing memory in general? Then came other questions that I needed to find answers for in my films about how many accumulated temporality do we live through simultaneously? How do we deal with a present that becomes instantaneously a past?

[Image from Ma’loul Celebrates Its Destruction]

This is what got me to discover different levels of memory as was the case with the film, Ma’loul Celebrates Its Destruction. These levels ranged from actual time to a mental one, to the fallouts of memory and belonging. There is also the issue of false memory and the writing of false history/ideological history. I had to choose documentary filmmaking in order to record “reality” and unpack it so I could restructure it cinematically. That is how I can wipe the borders between what is fictional and what is documentary and convey the poetic elements in our daily experiences. These, in my view, are the bases for writing poetry and recording reality.

IN: Is this what led you to make the film, Fertile Memory?

MK: Yes. Fertile Memory (1980) was the beginning of my cinematic experience. I captured what I loved. Women are the basis of the film and their memory is what embodies the Palestinian human experience. Men’s discourse is built on authority and hierarchy. Women live through the physicality of reality in all its details in their relation with men and children. They are at the center of where the dialectic between the victim and oppressor stands. If we look at Palestinian society, we find that it fell victim to colonialism and arrogant Zionist authority. The most important thing in the film was to target the dominant male discourse. The point of reference for Palestine became women as illustrated in the experiences of author Sahar Khalifeh and Ms. Roumieh Hatoum. In a society as poor as Palestinian society, this was the first independent experience from the dominant Palestinian discourse of the time. I wanted the film to be for women and Palestine and not about them. I wanted to show the humanity of things in this erased place: the trees, the light, the land, the birds, the children, the music of daily life. Documentary cinema in its simple technical demands is closer to Palestinian reality more than Hollywood cinema. The film brought us back to our human experience and emphasized the role of culture in not compromising that humanity. Our struggle against Zionism is not allowing it to erase our humanity. We do not want to deny the rights of the other but will not allow them to deny ours.

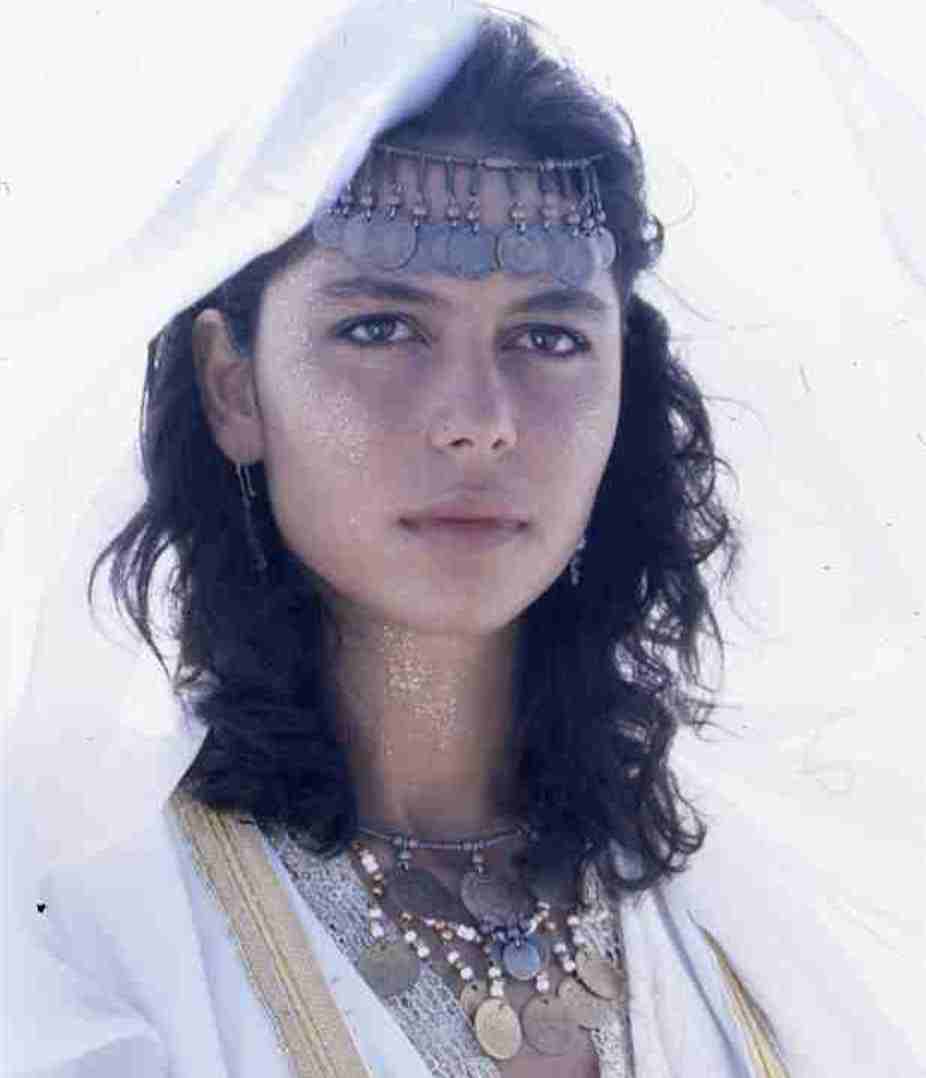

[Roumieh Farah Hatoum in Fertile Memory]

It was important for Palestine to show up on screen. It symbolized the land and had a leading role in the film. Despite our humble means we managed to bring the film to international audiences. The film raised questions not only about Palestine but about documentary cinema more generally, and what it means for documentary films to express the inner life of real characters. Fertile Memory is a film about how to live under occupation through a portrait of two women who struggle, each in her own way, to defend her right as a Palestinian and as a woman.

IN: How did you start working on the film, Ma’loul Celebrates Its Destruction?

MK: The idea for the film came through the filming of Fertile Memory. In the late 1960s, I used to work at a Volkswagen garage in Haifa and the manager was from the destroyed village of Ma’loul. He lived in Nazareth at the time and we used to travel to work together. Whenever the car would pass by the pine tree forest named after the ill-remembered Lord Balfour of the ominous promise (in 1917), he would tell me, “That is Ma’loul, my town!” I could not see anything except for the pine trees. As you know, many of the inhabitants of the Palestinian villages destroyed by the Zionist forces (during the 1948 war) sought refuge in Nazareth. They maintained their rural identities and refused to be called except after their villages; this was Safouri, and that was Mjadelawi.

[Image from Ma’loul Celebrates Its Destruction]

In the end, I managed to see the church’s cross in between the trees. When I filmed my first film, Fertile Memory, in May 1980, Israel was celebrating its independence. The people from Ma’loul made that date into a memorial day for their Nakba (catastrophe). Israel’s independence day became their Palestinian Nakba. Ma’loul in this context symbolizes an existential experience that we lived through since we were kids. There was an essential contradiction. On the one hand, we had history lessons imposed on us by the Israeli educational curriculum, and on the other, we possessed the knowledge of our lived history. This contradiction that we see in the experience and memories of people from Ma’loul gave me the idea of making a film that speaks about this tragedy. People know the history of this land. It is their lived history. This history is different from the ideological discourse taught at school. Ma’loul was and still is engraved in the memory of its sons and daughters. It is now a forest wiped off the face of the earth but is still alive and not erased from the depth of their memory.

[Anna Achdian Condo in Wedding in Galilee]

IN: Is there a relation between your film, Wedding in Galilee, and the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982?

MK: Maybe indirectly. I wrote the scenario in 1984, we filmed in 1986, and the film was screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1987. Of course, the expulsion of the Palestinian liberation movement from Lebanon added another defeat and affected all of us. This created a crisis and new questions about the ability of the Palestinian national movement to continue. We entered into a period of loss and things looked as if they were collapsing like castles from sand. We were left with the cultural struggle that delved into the reasons for the defeat. My response was to make Wedding in Galilee. The film tells the story of a mukhtar (head) of a village who wants to marry his son in spite of the siege and curfew imposed by the Israeli military. The mukhtar was forced into inviting the military ruler and his officers to the wedding. I wrote the scenario following the structure of the Greek tragedy. The introduction to the tragedy is the challenge between the mukhtar (patriarchal father) and the military ruler (the authority of power and death). The latter said to the mukhtar: “You won’t be able to celebrate without permission from us!” This challenge makes the people the real heroes. They take initiative to reroute the helm of history. At the end of the film, people went out to the streets and forced the Israeli army out of the village. The film is a canticle of joy for what is human in Palestine: the child, woman, bride, and groom. The space and time are Palestinian, and I wanted the film to be a symphony, a collective opera.

IN: What about Canticle of the Stones?

MK: At the beginning of December 1987, six months after the first screening of Wedding in Galilee at Cannes, the popular intifada (uprising) started in the West Bank and Gaza, where thousands of children, men, and women lost their lives. I went at the beginning of 1989 to Jerusalem and the Occupied Territories looking for an entry point to make a film that talks about the stories of the martyred children who died defending their dignity against the occupation. The stone held by the child was more powerful than the weapon of the Israeli soldier. Yet the accumulation of killing and struggle united the Palestinian political discourse and everyone started speaking with the same vocabulary and nationalist expressions. This led to a decline in the spontaneous discourse that comes out of the heart of the human experience. This mattered to me more than the loud slogans. I wanted to concentrate on the relation between the human and the struggle, between the man and the woman, the present and the past, and how we develop from them a movement towards the future.

[Left to right: Makram Khoury and Bushra Karaman in Canticle of the Stones]

I wrote a poem in the voice of a man and a woman; two lovers in their forties who meet after fifteen years of separation. He was in prison and she left for the United States to study. This gave me the historic and mental distance and the fallouts in their memory that prepared for the historic background of the Intifada. I made a film where the fictional (theatrical) and lived reality (documentary) coexist. This was a new experience in cinematic production.

IN: What are your impressions of Palestinian cinema at the time?

MK: Unfortunately, I was the only film director in the Palestinian cinematic scene then. From the beginning of the 1980s and until the early 1990s there were no Palestinian film directors. In the 1990s, a number of directors emerged and contributed to enriching and expanding new cinematic themes and forms. They are from the “Oslo” generation and focused more on globalization. Despite the difference in quality, this was a great contribution to Palestinian cinema. I, in turn, became part of that group and made a number of films including, Forbidden Marriages in the Holy Land (1994). It is a documentary film that poses the question of marginalized couples that fall in love despite being from different ethnic or religious backgrounds. They suffer as a result of narrow definitions of nationality and religious violence that currently dominates the general scene in the Middle East.

[Image from Tale of The Three Jewels]

Tale of The Three Jewels (1995) talks about childhood in the Gaza Strip where reality is disparate and painful and children are struggling to preserve their right to be children. This was the first film to be made in Gaza. I insisted on making the film with Gazans as part of my commitment and solidarity. Marginalized Gaza has the right to enter into the modern world and preserve its human dignity. Through the child, Yousef, and his friend (beloved) Aida, I wanted to recognize the individual and their right to experience, be creative, and play an essential role in building society.

[Images from Tale of The Three Jewels]

IN: Did you make the film, Route 181: Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel, in response to the Oslo Agreements?

MK: In the beginning of 2000, the second Palestinian intifada broke out which resulted in unbearable violence. The Arab and Israeli political discourse started to slip more and more into racism. All the attempts and experiences by progressive Palestinian/Israeli or Arab/Jewish groups were defeated in the face of violence which predicted what we witness today of the Da‘ishi (of the so-called Islamic State) discourse and that of the radical right in Israel, Europe, and the West more generally. Eyal Sivan (a progressive Israeli filmmaker that opposes Zionism) and I wanted to make a joint project that could stand in the face of the racist discourse coming at us from all directions.

It was important for us to say that we did not want to eliminate the humanity of anyone. Neither the Jew is able to eliminate the humanity of the Arab nor the Arab is able to eliminate the humanity of the Jew. We were aware of the fact that it was impossible to overcome this crucial stage without civil wars that could bring disaster to the region. We crossed through the road bumps and the crisis of the “killing identities” that could no longer survive the rhythm of immense change. These changes are a product of deep demographic shifts and new consciousness built on the identity of the individual and not the group that we were accustomed to for thousands of years. It is a testimony to the end of collective societies based on religion, sect, tribe, clan or even ideological party affiliation, and the birth of new societies founded on citizenship where the individual plays an essential role in leading it to democracy.

We are witnessing a sociopolitical and intellectual struggle between the old world that does not want to die and the new world that is facing difficulty living in the midst of this crisis. This is our crisis and without equality between the North and South, West and East, rich and poor, how could we build a human world that takes into account these injustices?

The Zionist/Israeli society has become a point of reference in the Middle East and the world at large especially in the West. It is ironic that Zionist thinking is at the beginning of its decline. It lived through its “youth” for only seventy years. Yet, it will leave its mark (inheritance) to the remnants of the East that are tearing apart our region. The Zionist regime is becoming a point of reference for these forces: every tribal, religious or sectarian group wants to be like it. They all want killing identities based on the Zionist one: religious myth and historic reference built on false discourse and fabricated language.

As for the Western world and its empire that is also in the process of collapse, Zionism became its last colonial resort where they learn the latest technologies and art of war against Arabs and Muslims. This is how a mixed up situation gets to be created, where the strong dictates to the weak to become like them, and at the same time the strong identifies with the weak and tries to tame them. When each looses its “authenticity,” identity crises are created and they lose their image. They no longer know who they are and what they need to do: are we them or are they us? The Islamic fundamentalist becomes a caricature for the Jewish fundamentalist who in turn is a caricature of the Christian fundamentalist, etc. There is no difference between them except in how they kill, torture and exploit.

We are in need of a long halt in the face of our symbolic world that governs our consciousness: we are ruled by dead people and live in a world that only exists in our heads. We are incapable of performing the necessary mourning in order to separate the past from the present and the present from the future.

When Eyal and I went to film Route 181, we found ourselves like someone who is walking inside a deep wound, and on the edges of the wound there were different people in pain, each in their own way. The Israelis on the one hand, come from the wounds and blows of their cursed past, and here they are obliged to continue lying to themselves because they are aware of what they did against the Palestinian people and how they erased their world. Yet, they continue with the lie that is built on myths that have no place in the modern world and that is a trauma on its own. As for the Palestinians, they are unable to confront their miserable reality and attempt to understand what happened to them. How could they be responsible while living in a trauma that prevents them from seeing the light of truth?

When we started filming Route 181, we imposed clear cinematic and moral conditions on ourselves: not to insult or make fun of anyone; to have the encounter with people be spontaneous and without preparation; not to prejudge and to respect everyone even if they held despicable racist views.

IN: How can we overcome the current stage?

MK: In the film Zindeeq (2009), the main character is looking for himself and does not identify with power and violence. He knows that the source of the Palestinian tragedy is colonial power and violence. The salvation of oppressed societies does not emerge except through creativity, search for freedom, and commitment to the basic human condition. That means that all our points of reference need to be moral and legal. We need to search for other experiences like those of pacifist struggles in Poland and Czechoslovakia, and especially in South Africa where Mandela taught us a lesson on how to lead a moral struggle. Non-violent struggles are wonderful and in Zindeeq I tried to deal with this issue to prevent the Palestinian struggle from reaching the crisis of indefinite violence.

[Filming of Zindeeq]

This was a prediction of the violence that emerged in the aftermath of the initial experiences of what was called later the Arab Spring. The return of the main character in the film to his family’s and childhood house to find it collapsing and occupied made him realize the need to start mourning in order to understand what happened and what brought us to this situation.

Mourning the past is important because the past lives within us and prevents us from seeing the future. In Zindeeq as in our painful reality, the past is what governs us with its dead characters. Belonging that has no meaning does not produce creativity, and if it is tied to a dead past it will prevent us from posing basic questions and will paralyze the movement of history. I played myself as the main character in the film. I wanted it to represent the new modern Arab who needed to complete his mourning. There is a healthy relation between mourning and the need to separate from the symbolic and material inheritance of the past in order to reorganize our relation to the present. That is why we find that many families explode after the death of the father or mother because they did not mourn properly.

The emphasis here is on the renewed relation to things and not on forgetfulness. Old Palestine will not come back but mourning properly will allow us to see the Palestine of the future, the new Palestine that we strive to achieve. What I wanted to pose relates to what we want to do with the image of Palestine. Do we continue to repeat the same “story” and the same “questions” and in the same format?

[This interview was originally published in Arabic. It was translated into English by the interviewer. To read the Arabic version of the interview, click here.]